Winston Churchill, impressed by the action carried out by the German airborne forces in Crete in 1941, led to the formation of the first British airborne units. The first such unit was the Parachute Regiment, and the first operation was carried out by British paratroopers in 1942. A year earlier, the 1st Parachute Division was formed, and two years later (in 1943), the 6th Parachute Division. It is worth adding that next to these two divisions, there was also the 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade, formed in 1942. Both British parachute divisions had four to five parachute and glider infantry brigades and support units, such as anti-tank troops, a sub-unit of light tanks or engineering, and sapper units. British parachute troops fought both during the fighting in North Africa (1942–1943), during the landing in Sicily and southern Italy (1943), and during the fighting in Normandy (1944) or during the unsuccessful Operation Market-Garden (1944). They were also used during the forcing of the Rhine (1945) and in the last fights in Germany.

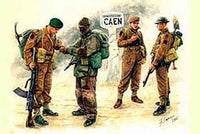

During World War II, the British Army formed a total of 43 infantry divisions. At the start of the war, the division's staff numbered approximately 13,800 officers and soldiers, while in 1944, this number increased to approximately 18,300 people. This significant change in the number of employees resulted primarily from the increase in various types of support units and not the increase in the number of infantrymen themselves. In 1944, the British infantry division consisted of three infantry brigades, each with its own headquarters, a staff platoon, 3 infantry battalions, and engineering divisions. It is worth adding that a single infantry battalion had approximately. 780 officers and soldiers and had numerous support units (e.g., a mortar platoon or a reconnaissance platoon). The division also included a de facto artillery brigade with five artillery regiments (including one anti-tank and one AA), a battalion of machine guns and mortars, as well as reconnaissance, communication, and sapper units. An important element in increasing the mobility of the British infantry division was its full motorization. The British infantryman's primary rifle was the Lee Enfield No.1 or No.4 rifle. As machine weapons, among others, Sten submachine guns, Bren manual machine guns, and Vickers machine guns were used. The most commonly used anti-tank weapons were the 40 and 57 mm 2- and 6-pounder cannons, and later also the 76-mm 17-pounder cannons. In turn, the main armament of the field artillery was a very successful howitzer, the Ordnance QF 25-pounder.

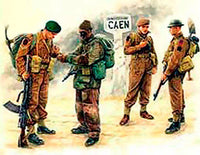

The Battle of Caen 1944 stayed carried out in the period from June 6/7 to July 19, 1944. The battle was fought between German troops and mainly British and Canadian units. It is assumed that during the entire battle, 7 infantry divisions, 8 armored divisions, and 3 heavy tank battalions were involved in the axis. On the Allied side, 3 armored divisions and 11 infantry divisions took part in the entire battle. The above numbers apply to units participating in the battle throughout its duration (June–July 1944), and thus smaller forces were involved in it at one time, especially at the beginning of June 1944. The Battle of Caen was fought shortly after the landing of the first Allied troops in Normandy (Operation Overlord), and its goal on the British-Canadian side was to capture this important city. The original Allied plan was to seize Caen on June 6, 1944, but it backfired. On the other hand, later attempts to encircle the city, undertaken by British-Canadian troops under the command of BL Montgomery, met with tough and decisive resistance from the German side, especially the 12th SS Hitlerjugend Division and the 21st Panzer Division. In early July 1944, after a series of unsuccessful encirclement attempts, the Allies decided to launch a frontal attack on Caen. With the involvement of significant air forces, the city was finally liberated on July 19, 1944, by the Allies.